3.3.

CURVES AND THEIR LINING

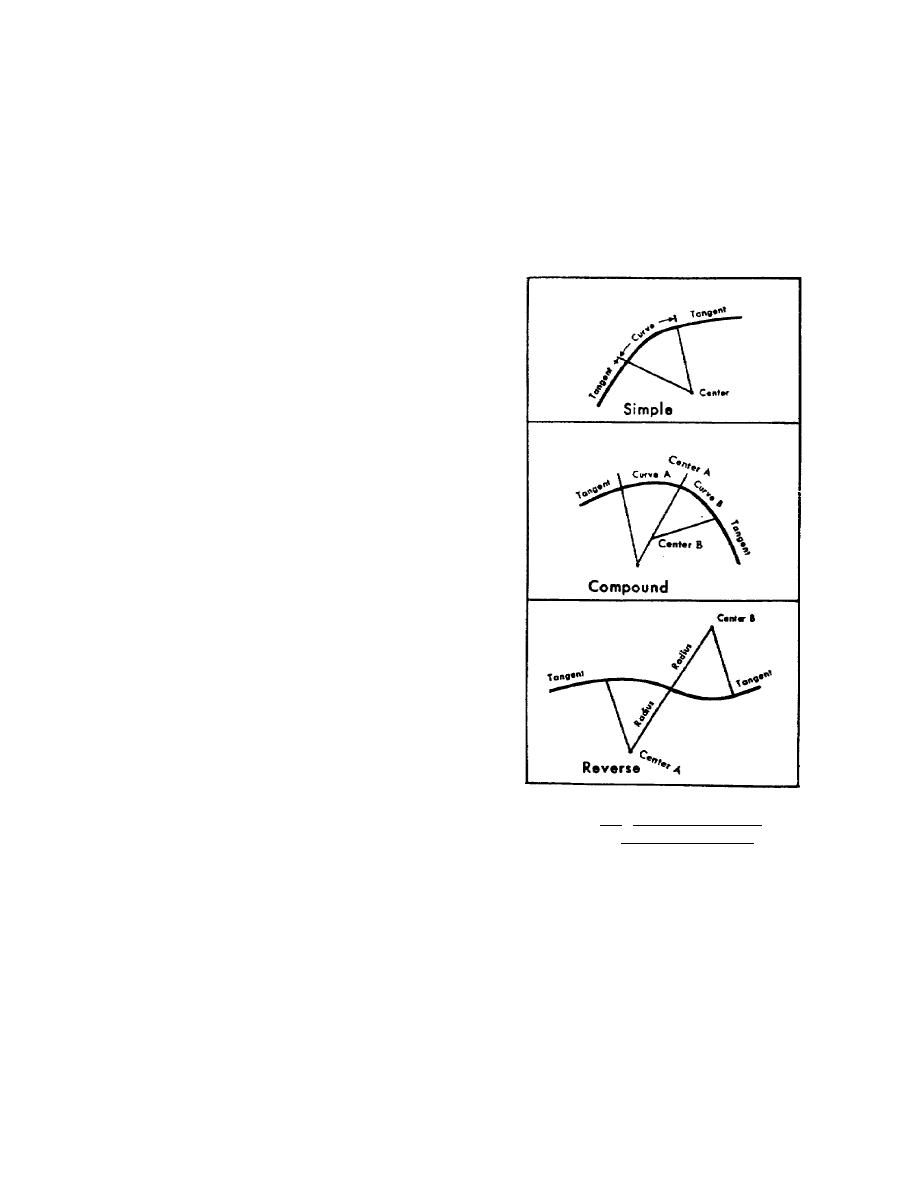

Curves may be classified as simple or circular, compound, or reverse. Study figure 3.1 as you read the

definitions to follow. A simple or circular curve is one with uniform radius; compound and reverse curves are

merely combinations of simple ones. A compound curve consists of two simple curves of different radii, both

bending in the same direction. A reverse curve is made up of two curves going in opposite directions, one

following on the other; the letter S is an example. Reverse curves require a tangent between them at least the

length of a locomotive. But a tangent of at least 300 feet makes construction and maintenance as well as train

movements easier.

The rail on the outside of a railway curve is

arbitrarily de -fined as the line rail, as paragraphs

1.25 and 1.26 explain. This is the rail that must first

be correctly lined. The inner one is then lined by

gaging it from the outer rail.

3.4.

EFFECT

OF

CURVATURE

ON

EQUIPMENT

The sharpness of curves is of extreme

importance. Locomotives and rolling stock must be

designed to operate on those over which they are to

travel. For example, a locomotive with a long, rigid

wheelbase is unable to negotiate sharp curves

without spreading the track gage. Curvature adds

additional resistance to a train's normal resistance to

movement. Naturally, this reduces the normal

tonnage capability of a locomotive just as a grade

does. Where curves occur on grades, this resistance

is further increased. If a locomotive's maximum

capability is the hauling of a 4,000-ton train up a 1.2

percent grade, it will stall if the resistance of a sharp

curve is superimposed on the grade. To enable this

type of locomotive to haul

Figure 3.1. Simple, Compound,

and Reverse Curves.

63

Previous Page

Previous Page