invariably weaker than the rest of the rail. When good track surface is lost, it is usually at the

joints.

All problems of track maintenance are accentuated

at the joints. When a train wheel passes over a

joint, a severe blow is delivered to the end of the

succeeding rail length, causing battered rail ends--one

of the more serious forms of wear to which rails are

subjected. Battered rail left in main tracks causes

rough riding, damage to equipment and lading, and,

eventually, pumping ties at joint locations. This

section explains the design, classification, installation,

and maintenance of rail joints, and the need for

compromise, insulated, and bonded joints.

3.25.

DESCRIPTION

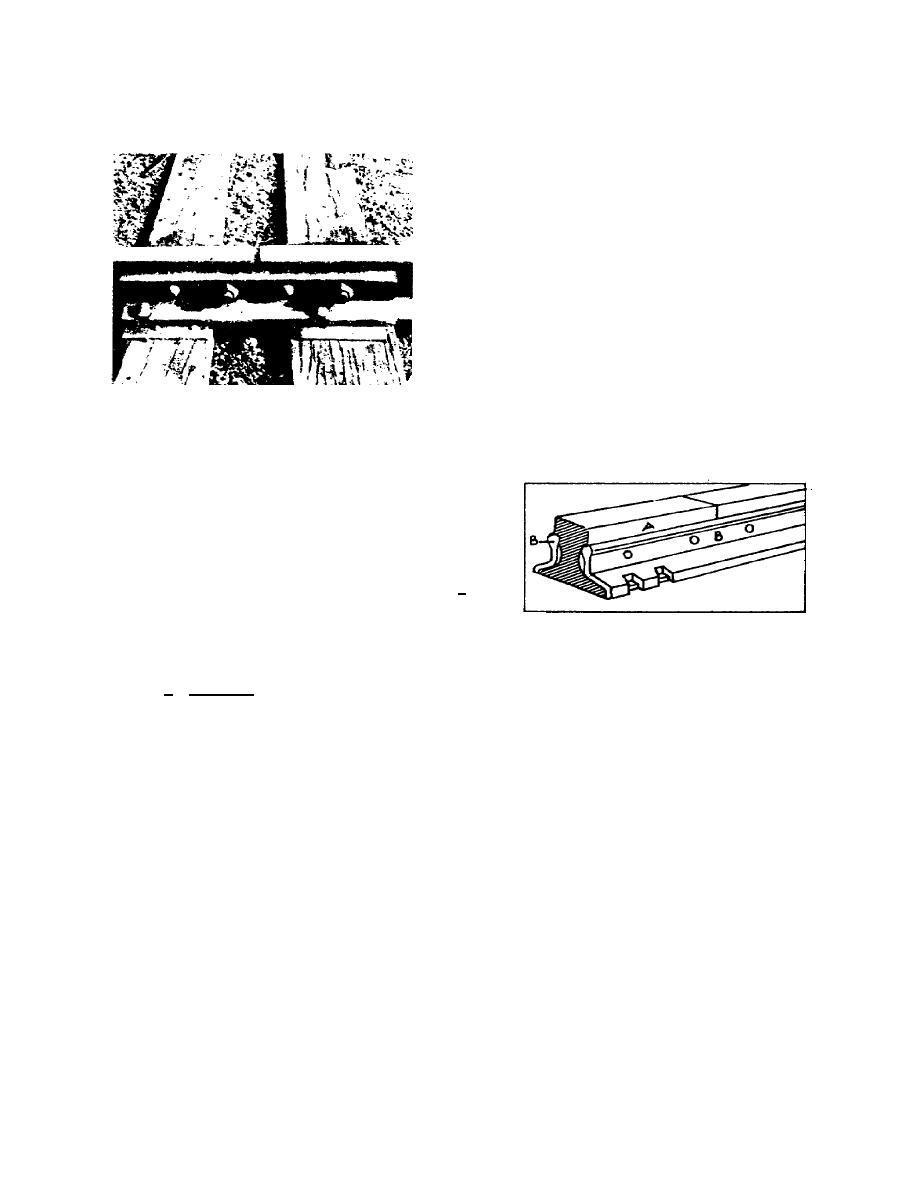

Where two lengths of rail meet, they must be spliced. The splice is made with a rail joint

consisting of a pair of bars bolted one on each side of

the two rails to be joined, as the sketch shows. In the

sketch, A indicates the rail; B the bars. Each bar

extends across the space between the rails. The bars

are variously called joint, splice, or angle bars. In this

text, they are referred to as angle bars (par. 3.26a).

The subparagraphs following describe the bars and the bolts used to join them to the rail,

the method of joining the bars to the rail, and the methods of joint support.

a. The bars. Either four-or six-bolt bars are used; the length of the bar determines the

number. Four-bolt bars are generally 18 to 24 inches long; six-bolt ones, 36 to 40 inches. The

six-bolt bars are more advantageous economically than the four-bolt ones. They provide longer

bar and rail life and preserve track surface at the joint. The four-bolt bars are simpler to install,

less expensive in cost, and lighter, and require fewer bolts. For these reasons, they are more

often used on military railroads.

62

Previous Page

Previous Page