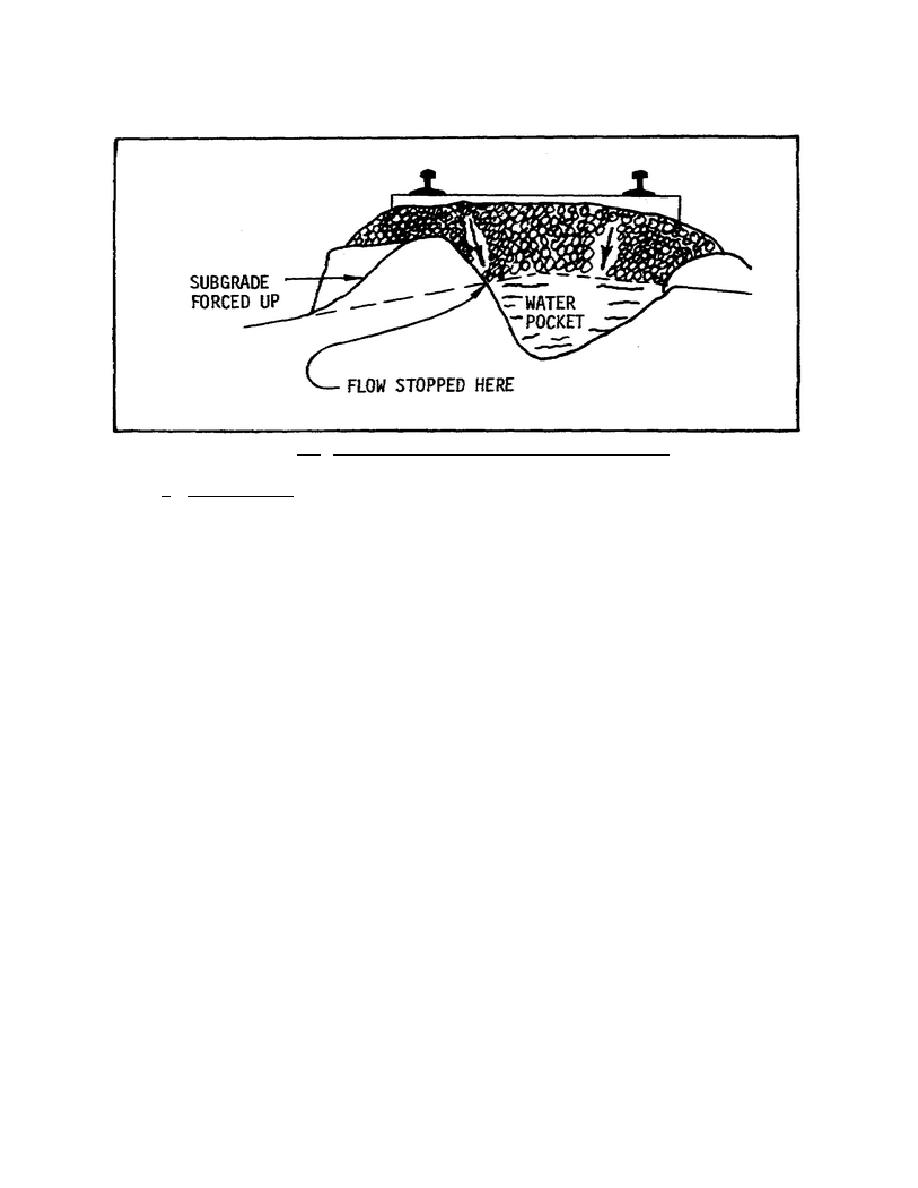

Figure 2.4. Drainage Obstructed When Subsoil Forced Up

b. Water pockets. Continually adding ballast under pumping ties eventually results in

large accumulations of porous ballast deep in the roadbed, sometimes to a depth of several feet,

surrounded by subsoil that is impenetrable to water. As water collects in the porous material and

cannot drain out, a water pocket forms. Obviously, a water pocket does not offer the same

resistance to train loads as solid roadbed. Such variable support results in uneven track and

spongy roadbed. Adding ballast, a penetrable material, to the soft spots in an attempt to achieve

uniform support only increases the size of the water pockets and forces the subsoil up into the

ballast section, cutting off any possible drainage from the ballast. Water pockets can present

problems in deep cuts, in fills, under heavy traffic, and in freezing weather.

(1) In deep cuts. Water pockets commonly occur in deep cuts where adequate

drainage is extremely difficult to establish. Such cuts are known as wet cuts. Water pockets in a

cut result in reduced train speeds and extensive track maintenance.

(2) In fills. Water pockets can form in fills in spite of the ease of drainage normally

expected to prevent the pockets. In fills or embankments, water pockets are dangerous and are

economic liabilities. In an embankment, water pockets may cause the fill to fail just as a train

passes over the track. Here they could be caused by using a small amount of porous material in

proportion to a large mount of impenetrable soil in the original construction of the embankment.

(3) Under heavy traffic. Operating numerous heavily loaded trains over a line with

poor ballast is often the reason for

28

Previous Page

Previous Page